Following on from my last piece about Gen X’s low-profile status when juxtaposed against Boomers and Millenials, I thought it was worth revisiting the murky subject of generational struggle. This time however, I will be focusing on the generation that just won’t die off: The Boomers.

These illustrious, seemingly all-powerful beings were born roughly between the early 40s and early 60s and came into their own at a time of great economic improvement and opportunity, greater music, and massive cultural change (i.e. the ’60s). Indeed, the popular picture that’s been painted of this era is one of revolutionary zeal, free spiritedness, and tremendous progress on Civil Rights; a time of renewed hope for mankind, following the bleakness of the Silent Generation. Of course, theirs was not a time without struggle as Vietnam and race riots dominated the news in the late ’60s while the ’70s saw staggering oil inflation, a decline in respect for politics (following Nixon), and the continuation of the Cold War. By the time of the 1980s however, the Boomers had found a sure footing in America as the dominant electorate and net of cultural values. And… that’s where things changed.

Now, it goes without saying that an entire generation cannot “sell out”; at least not in terms of its populace. With that self-evident notion hovering above us however, let’s consider how the radiant plumage of the ’60s got withered away and replaced with the shoulder pads, dodgy hair-dos, and new right or neoliberal values of the ’80s. Gone were the days of the “Hippie Revolution”; it was in with the “Commercial Revolution”, the “Reagan Revolution”, and a new mentality for an a generation graduating into their mid life.

What happened?

We’ve already touched on the struggles of the ’70s, if not the psychological and cultural repercussions they bore. Most people’s idealism will at some point be compromised by the practicalities of adult life when children, careers, and other factors come into the equation. The teens and young adults of the late ’60s simply grew up at some point. They were jaded, with that said, by the experiences of their time. While 1967 boasted the so-called “Summer of Love”, 1968 brought the “Summer of Hate” with revolutionary spirits leading to protests and then quashed protests. The loveable druggies of the Hippie era became, in part by reality (but also by the Media and politicians) the junkies of the following decade. Lyndon Johnson’s progressive agenda was torn asunder when Vietnam clouded his resume, not to mention the rise of Nixon (who hated Hippies and started the War on Drugs). With the sullen decline of this spirit in the ’70s (the decade of “Malaise”), it was no wonder why many Boomers were ready for a fresh start with the ’80s.

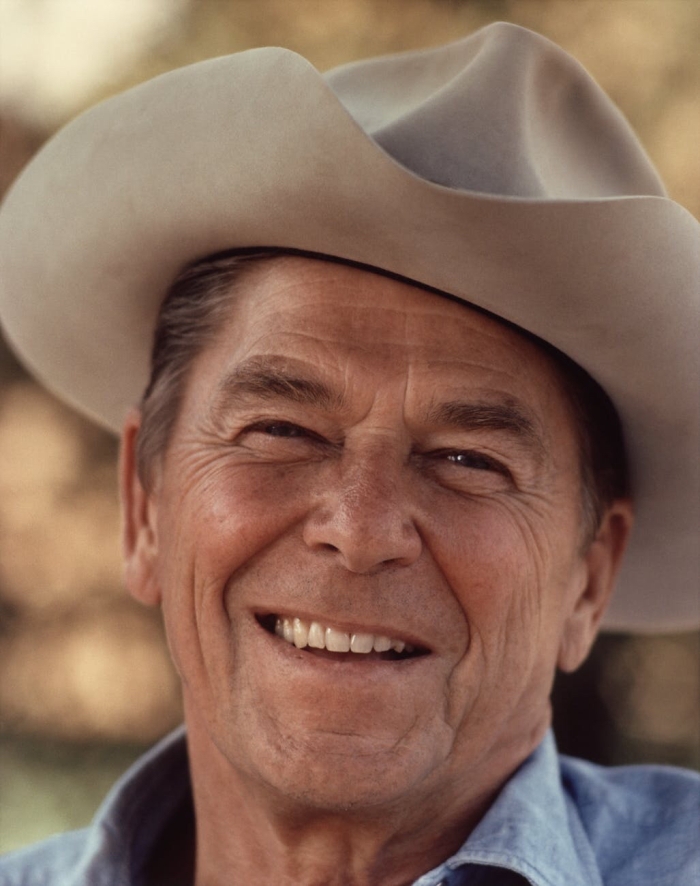

Ronald Reagan was able to sell that “fresh start” for many. Whilst his administration pushed America on a right-wing trajectory (it’s largely followed since) that would actually (in years to come) negatively affect the majority of Americans, he was able to sell it with a winning smile and the profile of a true leader. Enough Americans believed things were improving (having faced the “tough love” years of the Carter Administration) and voted him back in in 1984 as well as his successor, George H.W. Bush in 1988. The Democrats, in meek response, basically followed the New Right to the centre, whereby they could get a New Democrat-type politician into power with Bill Clinton in 1992 and so on… Politics aside, the point is that Boomers, having taken the largest share of the electorate by the 1980s were the ones to benefit from the initial economic upturn. Thus, even a mantra like “Greed is Good” (meant as a warning from Oliver Stone in 1987’s Wall Street) came to exhibit a twisted kind of wisdom for its age.

Bruce Gibney, author of A Generation of Sociopaths has been particularly critical of this turn of events. Speaking in an interview with Vox at the time of the book’s release, he said:

“Starting with Reagan, we saw this national ethos which was basically the inverse of JFK’s ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.’ This gets flipped on its head in a massive push for privatised gain and socialised risk for big banks and financial institutions. This has really been the dominant bomber economic theory, and it’s poisoned what’s left of our public institutions.”

The “Trickle-Down” economic model has been something of a “greatest hits” piece for the GOP since the 1980s. It would be foolish to state however that Boomers knew what they were in for with such changes. Even the politicians of the time, bent on conservative policies, couldn’t have known. With that said, that particular decade did set a damaging tone for what was to follow. The future of subsequent generation’s retirement funds, college loans, mortgages, and more were determined by what was set out then. At least in the 1970s, when there were economic struggles, there was some measure of co-ordination between Republicans and Democrats to balance out the extremes of either side that have increasingly flourished since. In many ways, it was a time of more liberal economic and political thinking.

The ’80s saw the rise of modern commercialism and a quasi-sanitised media too. Malls replaced high streets and new kinds of products lined the window faces of the shops built within. Movies of the ’70s, built on morally ambivalent antiheroes and dark realities faded from popularity as likeable heroes again took the screen. “Just Say No” and other family-friendly values and slogans helped push cheesy sitcoms to the fore. CDs saw the introduction of “Parental Advisory” stickers with censorship prevailing in the MTV era. Language and content were closely monitored on TV. It was a different kind of political correctness, to what we’re used to today, buoyed mostly by the New Right with puritanical leanings. All that is not to say great art wasn’t born out of that decade because it was but it was certainly symptomatic of a new way of refining the cultural values of the time.

American culture naturally moved on from the ’80s, with some persuasion from Gen X and subsequently Millenials in the following decades but by the mid-late ’90s, Boomers had effectively seized the reigns of power, which they still have tremendous persuasion over.

It is a harsh indictment, yes, and perhaps one a millennial, such as myself should be careful about castigating. As aforementioned, it’s generally the case that people will have different concerns in their 20s to what they have in their 40s. And the latter group, having moved up the career ladder, will have more money and more likely to grow conservative. People in their 20s want to see change. People in their latter years, less so. Plus, we’re not the first generation to think we know better or are “with it”. As Holly Scott put it in The Washington Post, of this generational divide:

“Young radicals believed they were ushering in a new America, and those over 30 were hopelessly out of touch and not to be trusted. Today’s youths have ‘Ok, boomer’. The youths of the 1960s had a different taunt: Mr. Jones, derived from the Arron saint of the youths, Bob Dylan, who sang, ‘ something is happening here but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?'”

Perhaps, like the Boomers, we are destined to meet a dead end, to hit a brick wall? Perhaps each generation is bound to retrace the same, familiar patterns if within a different context? And perhaps still, as Thomas Jefferson put it, “every generation needs a new revolution”.